Teaching kids about relevance

...using tricky math problems. Inspired by the philosophy of meta-rationality pioneered by David Chapman.

For those of you who are not familiar with Chapmannian1 meta-rationality, well… it’s a lot of things, very important things. Chapman’s website and associated Substack deep-dive into topics ranging from the Copernican revolution to the team that developed penicillin as a usable mass-produced drug. Chapman sees an inner unity to these topics — something he calls meta-rationality, a practice that goes beyond classical rationality to engage with the fundamental nebulosity of real human problems. Chapman’s work is an utterly unique and extraordinary edifice that I highly recommend spending a whole lot of your free time on. If you are a knowledge worker of any kind, it’ll have immediate material benefits to how you approach your job, and if you’re just a curious person (this is why you’re reading my Substack), you’ll have your mind expanded a lot.

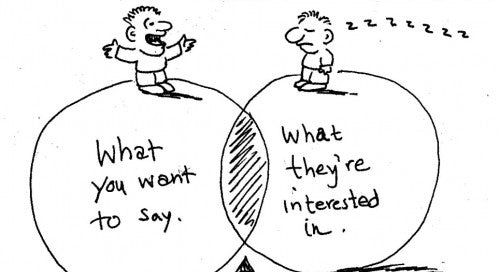

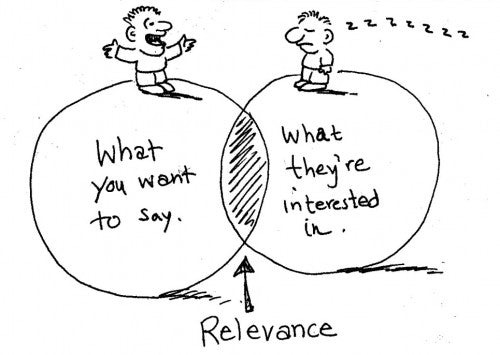

In this post, I’m going to touch upon what I consider to be the most important meta-rational theme, the concept of relevance, and how awesome it will be when we bring it to early childhood education.

Relevance in general is “what things are about.” In a more formal or technical context, relevance is about what “counts” in the formulation of a problem. This is a central question of modernity! Relevance is a sort of compass orienting us within the very high-dimensional space of possible solution architectures to any human problem, showing us the shape of the complexity-accuracy tradeoff so we can pick the appropriate point along that tradeoff for our current purposes. Chapman’s site title, In the cells of the eggplant, refers to the “trick question” of whether there is water in a refrigerator when an eggplant is inside. Of course there is — there’s water in the cells of the eggplant — but the deeper question is whether this water counts, which depends on why the question is being asked. In other words, it’s about relevance.

Since relevance is so important, it seems like a really good idea to teach kids about it and train them to consider it when solving problems. But Chapman’s blog is very heady, and the concepts seem to be aimed at an audience of intelligent adults. So what can be done on this front? More than you might think. I’ve recently taken to asking my daughter word problems like “if John has five apples and Bob has three oranges, how many apples do they have altogether?” Kids predictably assume mistaken things about these problems. They think that the problem…

… has no relevant intellectual content other than numbers

… is asking them to do something they’ve recently been taught, regardless of the words on the page

… follows the pattern of a previous problem

When kids encounter these “trick” problems — which are really not trick problems at all, but encounters with the fundamental problem of relevance that pervades modern life in every occupation — and find out that none of their assumptions are true, they’re initially shocked, but soon become delighted. Their brains light up. They become fascinated by math. Starting yesterday, my daughter is now begging me for math problems on every drive. For her, these trick questions are a welcome reprieve from the necessary but endless rigors of skip-counting and memorizing what numbers come after what other numbers.

Adults love these problems too, and readily create new ones. I ran a space last night where I showed off my daughter’s new abilities, and a random guy on the space immediately asked an awesome question: if you cut one apple into three pieces, and another apple into two pieces, how many pieces do you have? This stuff catches fire with people the moment you suggest it.

In short, I think relevance, and meta-rationality in general, are poised to come out of nowhere and eat education. And the sooner we do it, the better off college kids will be. Especially the sort of kids who get complex calculus word problems wrong because they “don’t know what the problem is asking.” Of course they don’t know, because they were never taught how to navigate relevance challenges. Let’s fix that.